The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) stands as an iconic institution in the global financial landscape. Situated in the heart of New York City’s Financial District in Lower Manhattan, it holds the distinction of being the world’s largest stock exchange when measured by market capitalization, exceeding an impressive $28 trillion as of July 2024. Owned by the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE), the NYSE serves as a central hub for the buying and selling of stocks, facilitating the crucial process of capital raising for corporations. This marketplace provides a platform for public companies to offer their shares to investors, thereby increasing the liquidity of their stock and enabling broader access to capital for expansion and growth. The sheer scale of the NYSE’s market capitalisation firmly establishes its dominant position within the international financial system, attracting major companies globally seeking the prestige and access to a vast pool of investors that listing on this exchange provides.

Beyond its function as a trading platform, the NYSE holds immense global significance. It is a cornerstone of international finance and trade, playing a pivotal role in the overall health of the global economy. The exchange facilitates the movement of capital, which is essential for driving economic growth and fostering job creation worldwide. Furthermore, the performance of the companies listed on the NYSE is often seen as a reflection of the broader economic climate, making it a closely watched indicator by investors, policymakers, and businesses across the globe. The very location of the NYSE on Wall Street has become a worldwide symbol of high finance and investment, deeply ingrained in the collective consciousness as the epicentre of global financial activity.

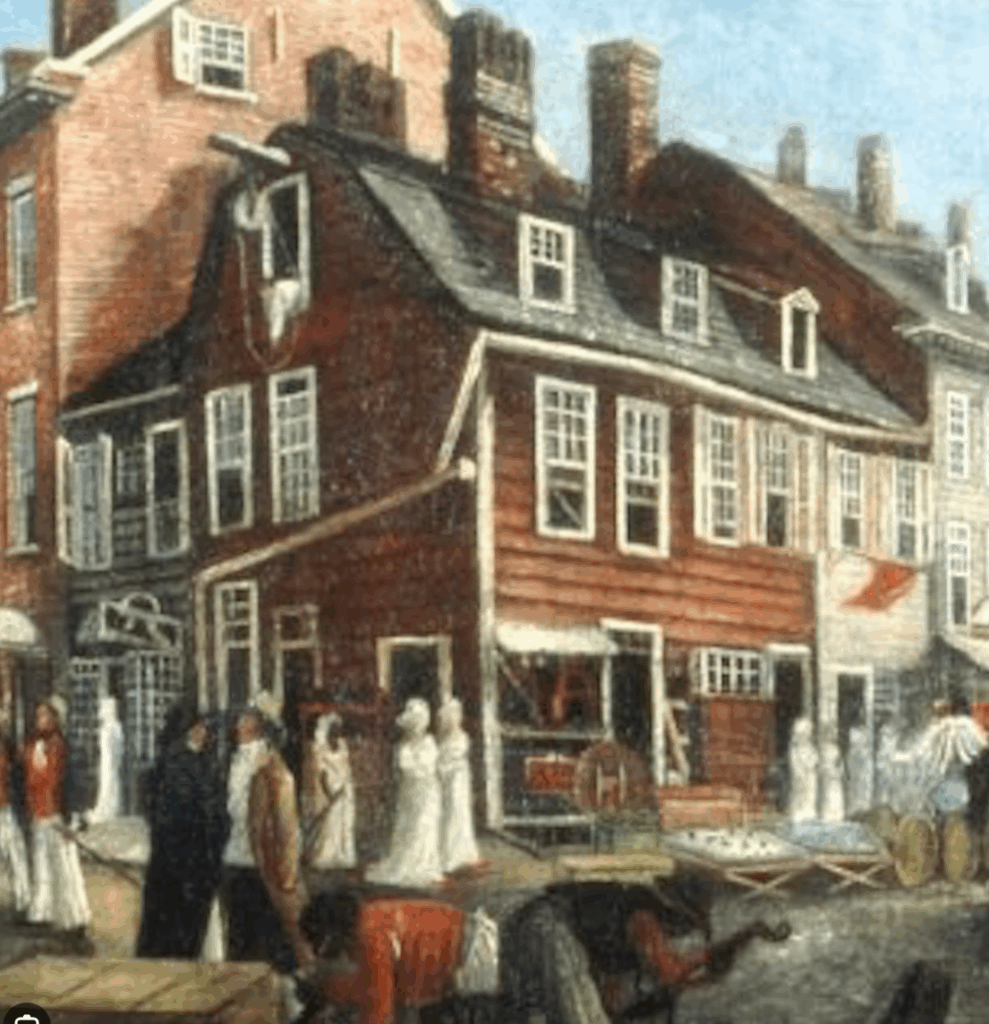

The story of the New York Stock Exchange begins in 1792 with an informal gathering of 24 stockbrokers under a buttonwood tree on what is now Wall Street.

On May 17th of that year, these brokers and merchants signed the Buttonwood Agreement outside of 68 Wall Street. This simple act marked the official beginning of organized securities trading in the United States. The agreement laid out the fundamental rules for how stocks could be traded among themselves and established a set commission rate of 0.25% for their services. By signing this document, these 24 individuals became the first members of what would eventually evolve into the NYSE. Among these initial members were individuals as well as firms, such as Armstrong & Barnewell. This initial step, though seemingly modest, established the foundational principles of organised trading and cooperation among brokers in the nascent American financial market.

In its early days, trading was conducted outdoors, under the shade of the buttonwood tree that gave the initial agreement its name. As the number of brokers grew and trading activity increased, they later moved their informal meetings to nearby coffeehouses, a common gathering place for merchants at the time. One such location was the Tontine Coffee House.

Initially, the scope of trading was limited to just five securities, primarily consisting of stocks from two banks – the Bank of New York and the Bank of North America – along with three types of state bonds. Notably, the first company to be formally listed on the NYSE was the Bank of New York, highlighting the early importance of financial institutions in the developing American economy. The early focus on government securities and the Bank of New York reflects the immediate financial needs of the young United States and the pivotal role of banking in facilitating economic growth. The Bank of New York, founded by Alexander Hamilton, further underscores its significance in the nation’s financial history.

As trading activity continued to expand, the need for a more formal structure became apparent. In 1817, the brokers established a permanent location at 40 Wall Street. The increasing activity in the stock market prompted the brokers to create a formal organisation with a constitution and established rules. On March 8, 1817, they officially adopted a constitution, giving birth to the New York Stock & Exchange Board, which served as the direct precursor to the modern NYSE. From its inception as a formal entity, the organisation implemented regulations to govern trading practices, including detailed rules for conducting business and imposing fines to maintain order among brokers. This move also included adopting restrictions on manipulative trading practices, indicating an early understanding of the importance of market integrity. Furthermore, the newly formed board began renting space specifically for securities trading, marking a departure from the informal setting of the Tontine Coffee House. This transition to a formal organisation with a constitution and dedicated trading space was a critical step in the NYSE’s evolution, demonstrating a growing understanding of the need for structure and regulation in the financial marketplace.

The 19th century witnessed significant growth and transformation for the New York Stock Exchange. Following the War of 1812, increased commercial activity across the United States led to a greater demand for capital, which in turn stimulated trading on the exchange. The 1830s saw a surge in speculation surrounding railroad stocks, further fuelling the growth of trading activity on the NYSE. Throughout the century, the NYSE experienced rapid expansion, both in terms of its physical presence and the volume of securities traded. It expanded its physical space to accommodate the growing number of members and the increasing trading volume and adopted more comprehensive regulations aimed at ensuring fair trading practices. The NYSE also formalised the process of listing standardised securities, contributing to greater transparency and investor confidence in the market. This period of expansion, particularly driven by the burgeoning railroad industry, highlights the crucial role the NYSE played in channelling investment towards emerging sectors that were vital to the nation’s economic development. The ability of the NYSE to facilitate capital flow towards these industries underscores its growing importance as a central pillar of the American economy.

The 19th century also saw the introduction of crucial technological advancements that would forever change the landscape of the NYSE. In 1863, the organization officially adopted the name “New York Stock Exchange,” a name that has since become synonymous with global finance. A pivotal moment came in 1867 with the introduction of the stock ticker, a revolutionary invention that dramatically improved the speed and reach of information dissemination in the market. This technology allowed for the near real-time transmission of stock prices over telegraph lines, significantly narrowing the information gap between Wall Street and investors across the country. In the same year, 1863, the NYSE achieved another milestone by becoming the first exchange to publish daily trading prices and a comprehensive list of the securities being traded. Further enhancing market efficiency, telephones were installed at the NYSE in 1878, enabling faster communication between brokers and their clients. These advancements culminated in a significant milestone on December 15, 1886, when the trading volume on the NYSE surpassed 1 million shares in a single day for the first time. The adoption of technologies like the telegraph and the ticker tape marked a fundamental shift for the NYSE, transforming it from a localised trading venue into a national marketplace by enabling quicker and wider access to vital trading information. This technological leap played a crucial role in establishing New York as the dominant financial centre in the United States, surpassing other exchanges like Philadelphia.

Despite this growth, the latter part of the 19th century was also marked by periods of financial instability. Securities trading during this era was susceptible to panics and crashes, highlighting the inherent volatility of these early, less regulated financial markets. Notable examples include the Panic of 1873 and the Panic of 1893. These recurring financial panics underscore the need for mechanisms to prevent widespread economic disruption and likely contributed to the growing discussions and eventual implementation of more robust regulatory frameworks in the 20th century. These events would have had a significant impact on investors and the broader economy, highlighting the risks associated with less regulated markets.

To accommodate its expanding operations, the NYSE also saw the need for larger and more modern facilities. In 1865, the exchange moved to a new location at 10 Broad Street. However, due to the rapid growth in trading volume and membership, this building had to be expanded multiple times throughout the latter half of the 19th century. By 1881, the expanded quarters offered improved ventilation and lighting, along with a larger board room to facilitate the growing activities of the exchange. Yet, even with these expansions, the building proved insufficient for the overcrowded NYSE by 1885, indicating the sustained and rapid growth in trading volume and the increasing importance of the exchange as a central marketplace for securities. The continuous need for physical expansion throughout the 19th century clearly demonstrates the NYSE’s increasing prominence in the financial world.

The 20th century brought both unprecedented booms and devastating busts to the New York Stock Exchange, alongside significant regulatory changes that reshaped its operations. In 1903, the NYSE moved once again, this time to its iconic location at 18 Broad Street. At the time of its opening, this new building was the largest indoor space in the United States, a testament to the scale and importance the exchange had achieved. The 1920s, often referred to as the “Roaring Twenties,” saw a period of significant economic growth and a booming stock market, fuelled in part by widespread speculation. However, this era of exuberance came to a dramatic end with the stock market crash of 1929. Black Thursday, on October 24th, followed by the even more devastating Black Tuesday on October 29th, marked a turning point, signalling the abrupt end of the bull market. The crash, which saw the Dow Jones plummet by significant percentages (for example, over 12% on Black Tuesday), is widely considered to have been a major contributing factor to the ensuing Great Depression. On Black Tuesday alone, a record-breaking 16 million shares were traded, a volume that would not be surpassed for nearly four decades. The dramatic rise and fall of the market in the 1920s and the subsequent crash laid bare the inherent risks of an under-regulated financial system and had profound and long-lasting economic consequences, leading to a significant increase in public demand for government oversight and reform.

The catastrophic impact of the 1929 crash led to a fundamental shift in the approach to financial markets, ushering in an era of increased regulation. The government recognized the necessity of overseeing securities trading to protect investors and prevent future economic calamities. This led to the passage of two landmark pieces of legislation: the Securities Act of 1933 and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934. The Securities Act of 1933, often referred to as the “truth in securities” law, aimed to ensure greater transparency and prevent fraud in the sale of securities by requiring companies to register their offerings with the government and disclose all material information to potential investors. Building upon this foundation, the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 established the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), a powerful regulatory body tasked with overseeing and regulating the entire securities industry, protecting investors from fraudulent activities, and governing transactions in the secondary market. The creation of the SEC and the enactment of these Securities Acts marked a decisive move towards a more regulated financial market designed to safeguard investors and prevent the recurrence of crises like the one in 1929.

Throughout the 20th century, the NYSE continued to embrace technological advancements that transformed its operations. While the stock ticker had already revolutionised information flow in the 19th century, the 20th century saw further significant developments. Telephones, introduced in the late 19th century, became increasingly integral to trading. However, the latter half of the century witnessed an even more profound shift with the introduction of computers in the 1960s and 1970s, paving the way for electronic systems of trade execution. A significant step in this direction was the introduction of the electronic trading platform known as “SuperDOT” in 1984, which further modernised the exchange’s infrastructure. By the end of the 20th century, while the iconic trading floor still played a role, electronic trading was becoming increasingly dominant, driven by the need for greater speed, efficiency, and accessibility in the market. This gradual but transformative shift from manual, open outcry methods to increasingly sophisticated electronic systems was a defining characteristic of the NYSE’s evolution in the 20th century.

The history of the NYSE is punctuated by several key events that have left an indelible mark on its operations and the broader financial world. Major market crashes stand out as particularly impactful. The Wall Street Crash of 1929, often referred to as Black Tuesday, occurred between October 1929 and July 1932. During this period, the Dow Jones Industrial Average experienced a staggering 89% decline from its pre-crash peak, ushering in the era of the Great Depression. Decades later, on October 19, 1987, the market experienced another significant downturn known as Black Monday. On this single day, the Dow Jones plummeted by 22.6%, representing the second-largest one-day percentage drop in its history. The turn of the millennium saw the Dotcom Bubble burst between March 2000 and October 2002, primarily affecting the NASDAQ, which had experienced a significant rise followed by a sharp correction. The financial crisis of 2008, spanning from October 2007 to March 2009, was triggered by the collapse of the housing market and the sub-prime mortgage crisis, leading to a substantial 51.1% drop in the Dow. More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 caused a sharp market downturn, with the Dow Jones falling by 37% and leading to a temporary shift to fully electronic trading on the NYSE. These major market crashes have historically had a profound impact on the NYSE, often serving as catalysts for regulatory reforms, accelerating technological shifts, and significantly altering investor behaviour and market sentiment. The increasing use of circuit breakers and trading halts in response to sharp market declines reflects a learned strategy to mitigate panic selling and maintain market stability.

| Crash Name | Date(s) | Key Index Affected | Percentage Drop | Brief Description |

| Wall Street Crash of 1929 | Oct 1929 – Jul 1932 | Dow Jones | -89% | Triggered the Great Depression |

| Black Monday | October 19, 1987 | Dow Jones | -22.6% | Largest single-day percentage decline in US history |

| Dotcom Bubble Burst | March 2000 – Oct 2002 | NASDAQ | -75% (on NASDAQ) | Collapse of internet-based companies |

| 2008 Financial Crisis | Oct 2007 – March 2009 | Dow Jones | -51.1% | Caused by housing bubble and sub-prime mortgage crisis |

| COVID-19 Pandemic Crash | March 2020 | Dow Jones | -37% | Global pandemic led to widespread economic uncertainty |

Beyond market crashes, the NYSE has also experienced several significant closures and unusual events throughout its history. World War I led to the longest closure in the NYSE’s history, lasting from July 30 to December 12, 1914. In 1920, a bomb exploded outside the NYSE building on Wall Street, tragically killing 38 people. The exchange closed on June 13, 1927, to honour Charles Lindbergh after his historic transatlantic flight. Following the assassination of President John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963, the NYSE closed early and remained closed for his funeral. In 1968, a significant increase in trading volume led to a “paperwork crisis,” forcing the NYSE to close every Wednesday for several months to process the backlog of transactions. The exchange also closed on July 21, 1969, to commemorate the Apollo 11 moon landing. The terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, resulted in a four-day closure of the NYSE. More recently, Hurricane Sandy caused a two-day weather-related closure in October 2012, marking the first such multiple-day closure in 127 years. The NYSE has also been the site of unusual events, including a protest in 1967 when Abbie Hoffman led a group who threw fake dollar bills at traders from the gallery, and an altercation during the filming of a Rage Against the Machine music video in 2000 that led to a temporary closure and the band being escorted from the premises. Additionally, on May 6, 2010, the NYSE experienced a “flash crash,” the largest intraday percentage drop since 1987, highlighting the potential volatility of modern electronic trading. These diverse events, ranging from economic crises to global tragedies and even moments of national celebration, underscore the NYSE’s deep interconnectedness with broader societal and geopolitical developments. Even seemingly minor events, such as honouring a national hero with a market closure, highlight the symbolic significance of the exchange in American culture.

Today, the NYSE operates from its well-known location at 18 Broad Street and 11 Wall Street in Lower Manhattan. It comprises two interconnected structures and is owned by the Intercontinental Exchange (ICE). The original building at 18 Broad Street houses the main trading floor, while an annex at 11 Wall Street contains an additional trading space known as the Garage. The modern NYSE is not a single entity but rather encompasses multiple markets, including NYSE, NYSE American Equities, NYSE Arca Equities, NYSE National, and NYSE Texas, all operating on the integrated NYSE Pillar trading technology platform. It also runs options markets through NYSE American Options and NYSE Arca Options. This complex structure allows the NYSE to cater to a diverse range of securities and trading needs through specialized exchanges, all unified by a common technological infrastructure.

The NYSE employs a hybrid trading model, seamlessly blending the speed and efficiency of electronic trading with the traditional human interaction of a physical trading floor. The primary trading mechanism is a continuous auction format, where brokers act as agents for buyers and sellers, competing to secure the best possible prices for securities. Electronic trading systems play a crucial role in matching buy and sell orders in real time, enhancing transparency and market efficiency. Designated Market Makers (DMMs) are central to the NYSE’s trading operations, responsible for maintaining fair and orderly markets for specific securities, managing the opening and closing auctions, and providing liquidity when imbalances occur. The NYSE conducts three single-price auctions each trading day: the Early Open, the Core Open, and the Closing Auction, facilitating price discovery at critical points in the trading session. The standard trading hours for the NYSE are from 9:30 AM to 4:00 PM Eastern Time on weekdays. However, reflecting the increasing globalisation of financial markets, the NYSE also offers pre-market trading from 4:00 AM to 9:30 AM ET and after-hours trading from 4:00 PM to 8:00 PM ET, allowing investors to react to news and events occurring outside of regular trading hours. The hybrid nature of the NYSE allows it to leverage the advantages of both electronic and floor-based trading, providing a robust and adaptable marketplace for investors and companies. The growth of pre- and post-market trading highlights the trend towards extended trading hours to accommodate global investors and enable timely responses to market-moving information.

To ensure the quality and reputation of its listed companies, the NYSE has established stringent listing requirements that companies must meet and maintain. These requirements encompass both quantitative standards related to a company’s financial performance and size, as well as qualitative standards concerning its corporate governance practices. Quantitative standards include minimum thresholds for financial metrics such as aggregate pre-tax income, global market capitalization, the number of publicly held shares, and the number of shareholders. For instance, the NYSE has tests for aggregate pre-tax income over several years, as well as specific requirements for global market capitalization and revenue. There are also minimum share price and distribution requirements, specifying the minimum number of publicly held shares and shareholders a company must have. Additionally, the market value of a company’s public shares must meet certain established levels. Generally, a company seeking to list on the NYSE must also demonstrate an operating history of at least three years. Beyond these financial and operational criteria, the NYSE also has qualitative listing standards that address aspects of corporate governance, ensuring that listed companies adhere to best practices in areas such as board independence and audit committee composition. Finally, companies seeking to list on the NYSE are required to pay various fees, including an application fee, an initial listing fee, and ongoing annual fees. These rigorous listing requirements serve as a mechanism to ensure that only well-established and financially sound companies are traded on the exchange, thereby upholding its prestige and maintaining investor confidence in the integrity of the market.

The New York Stock Exchange plays a fundamental role in both the US and global economies, primarily by facilitating the crucial process of capital formation. It provides a platform for companies to list their shares and access capital from a wide range of investors, enabling them to fund expansion, innovation, and other growth initiatives. The NYSE acts as a vital gateway for companies seeking to raise money through the sale of stock, including through Initial Public Offerings (IPOs), which allow young and growing companies to gain prestige and access significant capital. By providing greater access to capital for listed companies, the NYSE fuels economic activity and job creation. This ability to channel funds from investors to businesses is a key driver of economic dynamism in both the United States and the world.

Another critical function of the NYSE is providing liquidity to the market. Listing on the NYSE gives a company’s stock greater liquidity, meaning it can be bought and sold more easily without causing significant price fluctuations. The exchange offers a central platform where investors can readily buy and sell stocks, ensuring that there is a continuous market for listed securities. The NYSE Group, as a whole, boasts the highest levels of liquidity in the US equity markets, making it an attractive venue for both individual and institutional investors. This high liquidity reduces transaction costs and encourages investment, contributing to the overall efficiency of the market.

The NYSE also plays a central role in price discovery. The electronic trading systems at the NYSE match buyers and sellers in real time, a process that aids in transparency and helps to establish fair market prices based on supply and demand. All transactions executed on the exchange are reported, providing transparency and enabling efficient market operations. By facilitating the interaction of buyers and sellers, the NYSE helps to ensure that capital is allocated efficiently throughout the economy, contributing to overall economic stability and growth.

Furthermore, the NYSE serves as a closely watched barometer of economic health. The performance of the companies listed on the exchange often reflects the overall state of the economy, providing valuable insights into economic trends and investor sentiment. Market changes are frequently measured using key indices such as the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the S&P 500, both of which are heavily composed of companies listed on the NYSE. As a result, the performance of the NYSE is a key indicator that investors, policymakers, and business leaders monitor to gauge the direction and strength of the US and global economies.

Beyond the well-known facts and figures, the history of the NYSE is filled with lesser-known details and anecdotes that offer a more nuanced understanding of its evolution. Initially, the exchange was not known as the New York Stock Exchange but rather as the New York Stock & Exchange Board. The name was officially changed to the New York Stock Exchange in 1863. Interestingly, the iconic building that currently houses the stock exchange was not constructed until 1903. For a year after the signing of the Buttonwood Agreement, the brokers conducted their trading activities under the shade of the buttonwood tree.

The NYSE has experienced some remarkable closures throughout its history. Notably, it shut down for over four months during World War I, marking the longest closure in its history. Before the heightened security measures implemented after the September 11th attacks, visitors were allowed to take tours of the building and observe the trading floor in action. In 2005, a single NYSE membership reached a record price of $4 million, highlighting the intense demand for access to the exchange at that time. The impressive façade of the NYSE building has an official name: “Integrity Protecting the Works of Man,” reflecting the values the exchange aims to uphold. The tradition of the opening and closing bells dates back to the 1870s, with the original bell being a Chinese gong.

In a surprising feat of engineering, the NYSE building became the first air-conditioned building in North America when it opened in 1903. During World War II, in 1943, the trading floor was opened to women for the first time as men were serving in the armed forces. Muriel Siebert made history in 1967 by becoming the first woman to gain membership to the NYSE. For many years, the NYSE also housed a private dining club for its members and guests, the Stock Exchange Luncheon Club, which operated on the seventh floor from 1898 until its closure in 2006.

The iconic bell that signals the start and end of the trading day has its own interesting history. Bells were first introduced at the Exchange in the 1870s with the advent of continuous trading. As mentioned, the initial choice was a Chinese gong, but in 1903, when the exchange moved to its current building, the gong was replaced by a brass bell. Today, each of the four trading areas within the NYSE has its own bell, all operated synchronously from a single control panel. Interestingly, the sound of the NYSE’s closing bell is actually trademarked, further emphasising its symbolic significance in the financial world.

In its earliest days, the NYSE saw trading in a very limited number of securities, with only five being traded initially. As previously noted, the first company to be listed on the exchange was the Bank of New York. Among the companies with the longest listing history on the NYSE is Consolidated Edison (Con Ed), which joined the exchange in 1824 under its original name, the New York Gas Light Company. These lesser-known facts offer a glimpse into the human and historical context of the NYSE, revealing its journey from humble beginnings to a global powerhouse.

In conclusion, the New York Stock Exchange has journeyed from a modest gathering of brokers under a buttonwood tree to its current status as the world’s largest stock exchange. Its history is a testament to the evolution of financial markets in the United States and globally. From its early days of informal trading to the implementation of sophisticated electronic systems, the NYSE has consistently adapted to the changing needs of the economy and technological advancements. Its enduring legacy lies in its pivotal role in facilitating capital formation, providing liquidity, and driving price discovery, all of which are essential for a healthy and dynamic global economy. As the financial landscape continues to evolve, with the increasing role of technology and the challenges of global competition, the NYSE will undoubtedly continue to adapt and play a crucial role in shaping the future of finance. The ongoing shift towards extended trading hours and the careful balance between electronic and floor trading exemplify its commitment to remaining at the forefront of the global financial marketplace.